6 Copyright

6.1 Introduction

Copyright provides legal protection for the creators of literary, scientific and artistic works for their creations. Copyright law protects a wide range of works, such as books, magazines, newspapers, plays, music, drawings, paintings, sculptures, architecture, photographs and films. But copyright is not limited to works in the field of the arts. More functional works, such as geographical maps, industrial design, computer programs, video games and original databases can also count on protection through copyright.

The purpose of copyright protection is to encourage creators to create new works and to give them the opportunity to negotiate a fee for the exploitation of those works. To that end, copyright gives creators of original works a temporary right that gives them exclusive control over the reproduction and distribution of their intellectual creations. This control is not unlimited. In certain cases, the law allows others to use their works without permission.

This chapter provides a brief overview of national and international copyright legislation in Legislation and regulations.

Subsequently, Copyrights – Copyright holders discuss what copyright entails, how it is obtained and to whom it belongs.

In Software Protection under Using IP for specific topics specifically the copyright protection of software is addressed. It will also briefly discuss other ways to protect software, including the possibility of obtaining a patent for software-related inventions.

6.2 Legislation and regulations

Like other intellectual property rights, copyright is territorially limited. In the Netherlands, copyright is regulated in the Dutch Copyright Act.

The Copyright Act has been frequently adapted in recent decades to European directives that aim to harmonize copyright within the EU. The most important EU directives are:

- Directive on copyright in the information society (Directive 2001/29)

- Directive on the legal protection of computer programs, in short: Software Directive (Directive 2009/24)

- Directive on copyright in the digital single market (Directive 2019/790)

Furthermore, there are a large number of specific EU directives that harmonize parts of copyright, such as the term of protection. There are now 14 directives and 1 regulation at EU level that regulate aspects of copyright and its enforcement. This allows some similarity to be found between the copyright laws of the various EU member states, but there are still important differences in protection at national level.

At international level, the most important copyright treaties are the Berne Convention of 1886, last revised in 1971, and the WIPO Copyright Treaty of 1996. The international protection of copyright is also regulated in the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement), an annex to the Agreement establishing the World Trade Organization of 1994. These treaties guarantee that copyrighted works are automatically protected in a large number of countries around the world. As of 2024, 181 countries are party to the Berne Convention.

6.3 Copyrights

The Copyright Act gives the holder of a copyright following exclusive rights:

- The right to reproduce (Article 13 et seq. of the Dutch Copyright Act)

- The right to publish (Article 12 et seq. of the Dutch Copyright Act)

The reproduction right is broad. It includes direct or indirect, temporary or permanent, complete or partial reproduction, by whatever means and in whatever form. Making adaptations and imitations in a modified form, such as the translation or film adaptation of a book, also falls under the reproduction right. Only temporary reproductions of a transient or incidental nature, such as on-screen & cached copies that take place when viewing websites and technical copies in the memory of a satellite decoder and on TV screens, are explicitly excluded from the reproduction right.

The publication right is also broad and relates to every situation in which a work is accessible to the public. This includes tangible acts of public disclosure, such as the distribution, rental and lending of physical copies of works, and intangible acts of public disclosure, such as ‘live’ presentations, public performances, broadcasts, satellite and cable transmissions and online availability via streaming or on-demand services.

All these activities are in principle exclusively reserved for the owner of the copyright. This copyright holder may authorise or prohibit others from performing such activities with the work. This permission is often granted by means of licences.

However, there are situations in which the law permits third parties to use works without the permission of the rights holders. For example, no permission is required for quoting from works, using works for caricature, parody or pastiche and copying for private use. Other exceptions permit use for educational purposes, lending, reading disabilities, public safety, criminal investigation and church singing or use by cultural heritage institutions or the media. Use under these exceptions is often permitted under conditions, including in some cases the payment of a fair compensation to compensate the copyright holder for the damage suffered. The cases in which copyright is limited are laid down in articles 15 to 25a of the Dutch Copyright Act.

As soon as a material copy of a work, such as a physical book, DVD or CD, has been sold in the EU by or with the permission of the copyright holder, the right holder cannot prohibit further trading of that copy. This makes second-hand sales and parallel import possible. This is called exhaustion (Article 12b of the Dutch Copyright Act).

Copyright is also limited in duration. Copyright expires 70 years after the year of death of the creator. In case of multiple creators, the calculation starts from the death of the longest-living creator. If the creator is unknown, copyright expires 70 years after the year of first ligitimate publication. Copyright on works that have not been made public expires 70 years after creation. More information on this topic can be found in article 37 of the Dutch Copyright Act.

6.4 Requirements of copyright

Copyright protects works within the broad domain of literature, science or art, provided that they are original creations.

Exempt from protection are:

- Technically or functionally determined forms

- Concepts, ideas and stylistic features

- Factual information

No formalities are required to obtain copyright protection.

6.4.1 Work categories

Copyright protects any work in the field of literature, science or art, regardless of the manner or form in which it is expressed. The copyright right act contains a non-exhaustive list of examples of works that are protected by copyright. This list includes not only literary, scientific and artistic works, but various types of creations in the cultural domain, as well as numerous functional works, including computer programs and databases.1 The full list can be found in article 10.

Because this list of work categories is not exhaustive, various types of creations are considered to be work. This concerns not only cultural, but also commercial creations, such as marketing and advertising material, product catalogues, manuals, instruction sheets and web content. But not every creation qualifies for protection. For example, case law shows that no copyright applies to tastes and scents, because their form of expression is not sufficiently precise and objectively determinable, and sports competitions, because they are too bound by the rules of the game. Furthermore, official documents, such as laws and regulations and court decisions, are exempt from copyright protection.

6.4.2 Mental creation

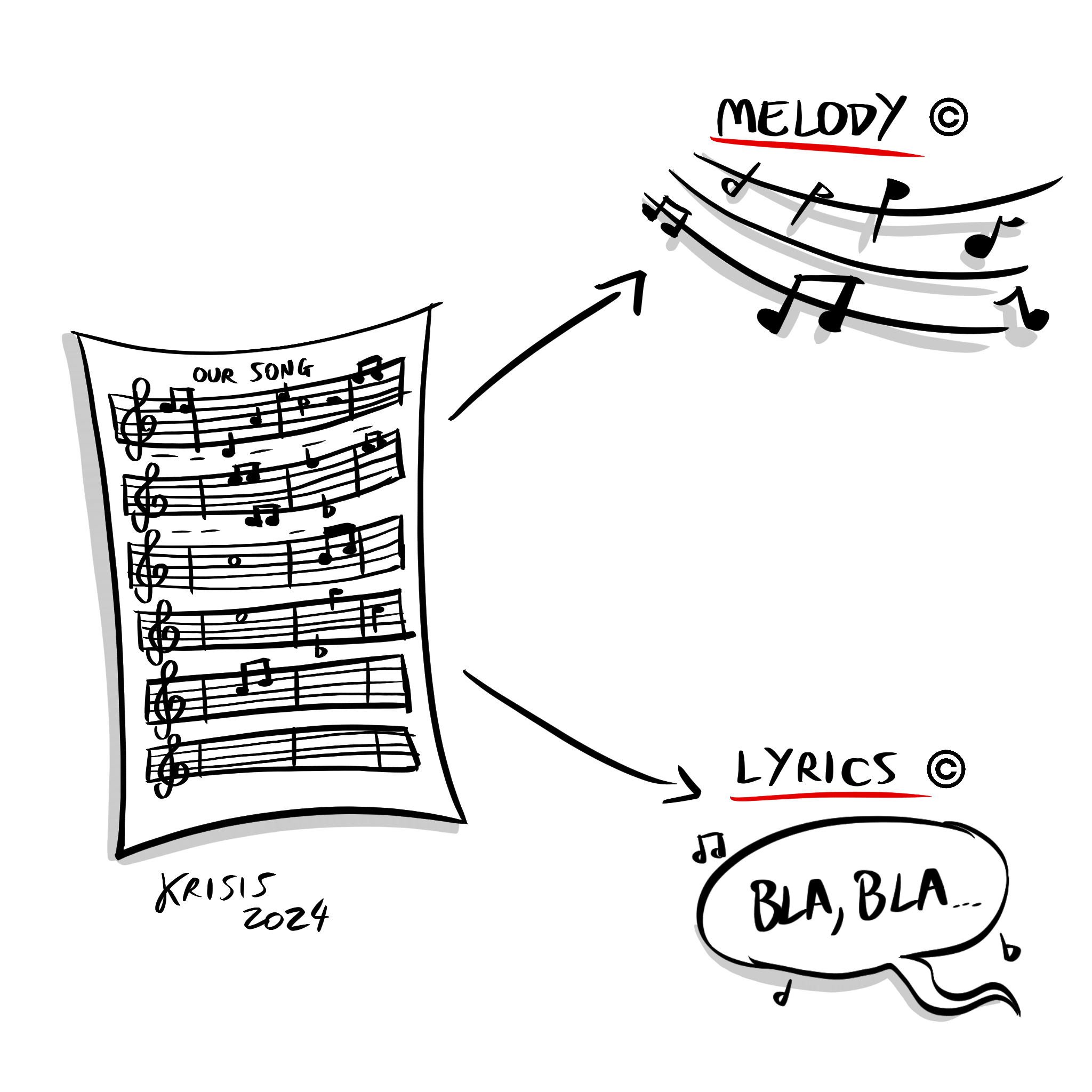

The tangible appearance of a work is not the essential object of protection. Copyright protects the mental creation which can be an untangible abstraction in which the work is recorded. It is therefore not the printed text that is protected, but the story that is told in that text. It is therefore the product of the human mind that enjoys legal protection. A work therefore does not have to be recorded in tangible form to be protected by copyright. On the other hand, the work must have been expressed in some way. Hence, a work that has only been performed but not recorded, such as a live improvisation by a jazz band, can therefore also be protected by copyright.

6.4.3 Originality

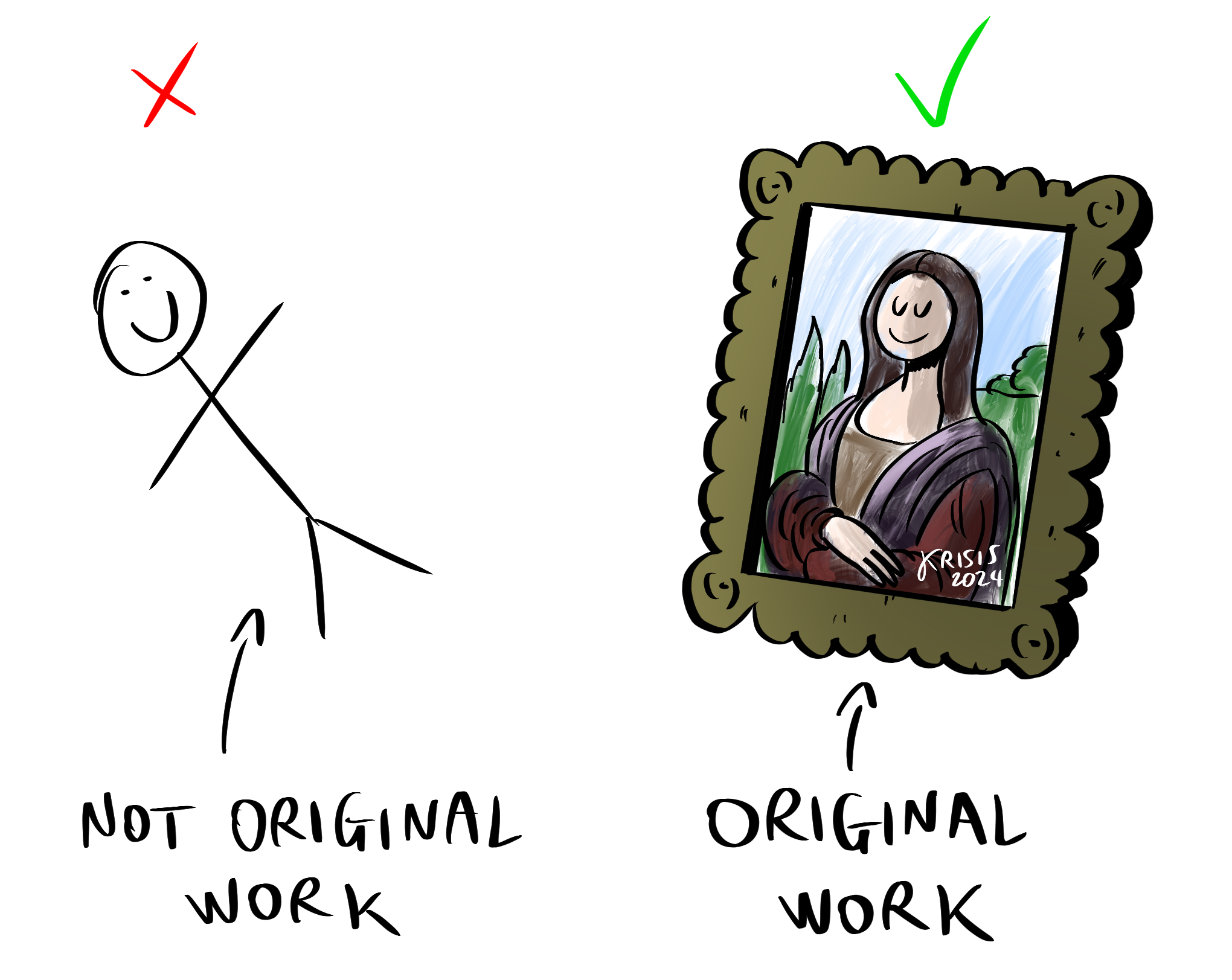

A work must have its own, original character and bear the personal stamp of the creator in order to be protected by copyright. This means that the form may not be derived from that of another work and must be the result of creative human labor and hence by certain creative choices. In other words, it must originate from the creator’s own intellectual creation, based upon free, creative choices.

The originality test does not have a high threshold, but there is a lower limit. If a work has a form that is quite trivial that no creative labor of any kind can be identified behind it, then it is not protected by copyright. Everyday work in which no creative choices can be discerned cannot be appropriated by copyright.

6.4.4 Technically or functionally determined shapes

Copyright requires subjective creativity. Shapes that are determined solely by technical or functional requirements cannot be protected by copyright, because the choice of that shape is necessary for obtaining a technical effect and does not reflect the subjective creativity of the creator. Everyone must be free to use such technical or functional shapes in a new design. To the extent that the creator has room to make creative choices outside of that and has also used that room, copyright does apply to the subjective elements of the product.

6.4.5 Concepts, ideas and stylistic features

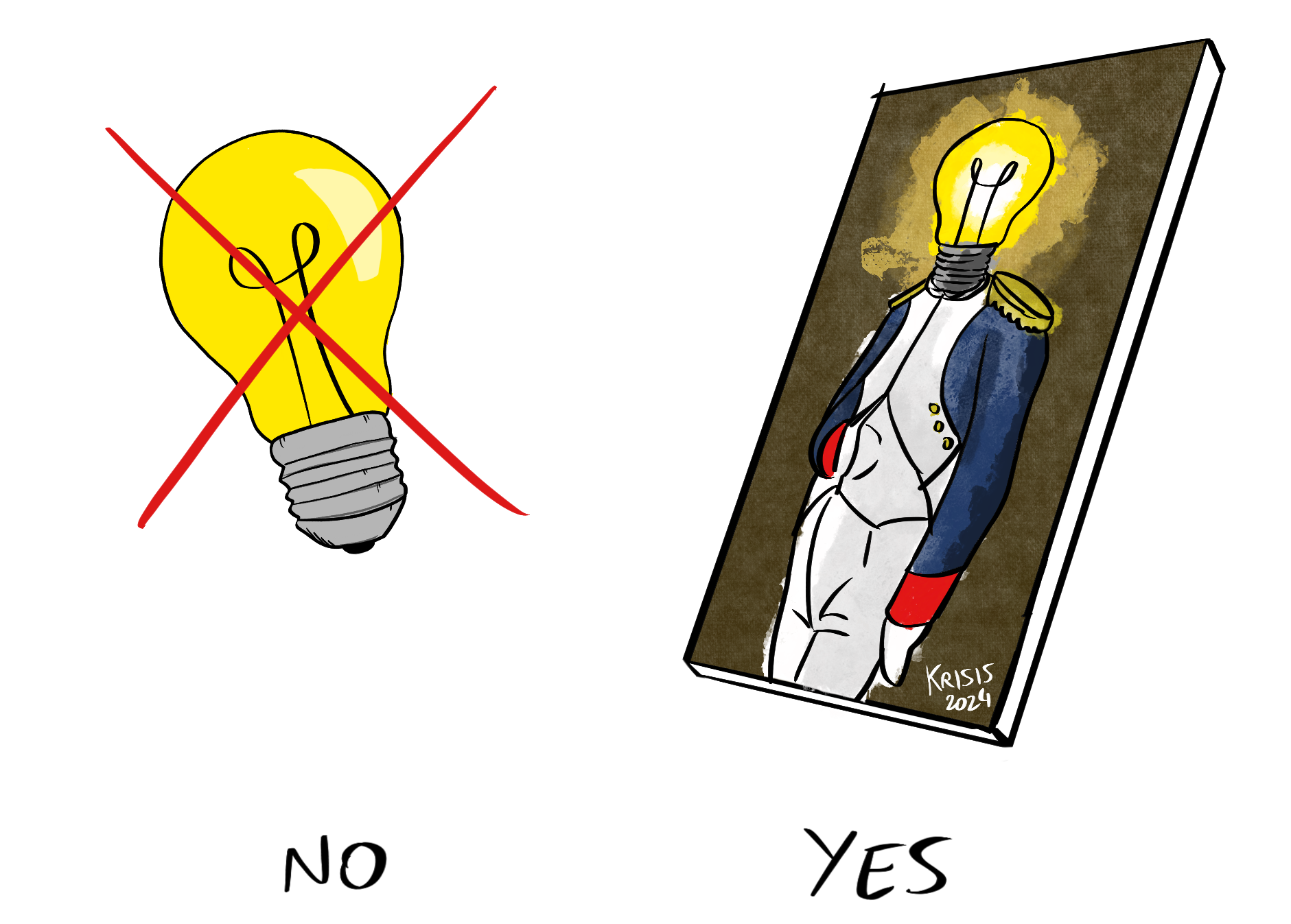

Copyright does not protect ideas, procedures, methods or mathematical concepts as such, but only the individual form in which the creator has expressed such abstractions in his work. The reason for this is that everyone must be free to elaborate on an idea or concept underlying a work. Ideas and concepts can therefore not be monopolized by copyrights. The same rationale applies to working in a certain style. If such abstractions could have been protected by copyright, this would restrict the freedom of creation too much and form obstacles to cultural developments.

6.4.6 Factual information

Objective facts, data and events as such are also not protected by copyright. The idea is that everyone should be able to report on factual information, whether it concerns news or scientific, historical or biographical facts, even if they have become available after much scientific research. Copyright does protect the subjective way in which a creator has expressed such information. Objective facts may therefore be copied, provided that the individual form in which the creator has expressed those facts is not copied.

6.4.7 No formalities required

The copyright act enables a creator to become the owner of the copyright of a certain work as soon as someone has created an original work of literature, science or art. No formalities, such as a registration, filing or filing a form or request, need to be performed to obtain copyright. It is also not mandatory to include a © sign on or with the work to show the creation of copyrighted work.

The advantage of copyright arising without formalities is that no deadlines need to be observed and that the creator does not have to worry about unintentionally losing protection as a result of not complying with formalities in time. The disadvantage is that there is no official register of copyrighted works. This sometimes makes it difficult for users to find out which works are protected by copyright and who is the owner or holds the copyright. On the other hand, it can also be difficult for creators and rights holders to prove that they hold the copyright on specific works. For the latter reason, in several countries it is possible to deposit a work and thus obtain evidence on a voluntary basis. Eg. in the Benelux this is possible via the i-Depot, which is maintained by the Benelux Office for Intellectual Property. Please note: a voluntary deposit only provides a date stamp but does not prove that the claim to copyright is valid.

6.5 Copyright holders

Copyright belongs to the creator of the work. In principle, this is the natural person who created the work. Under certain circumstances, a fictitious person, such as the employer or a legal entity, is considered the creator.

Copyright can also be transferred to other persons through transfer and succession.

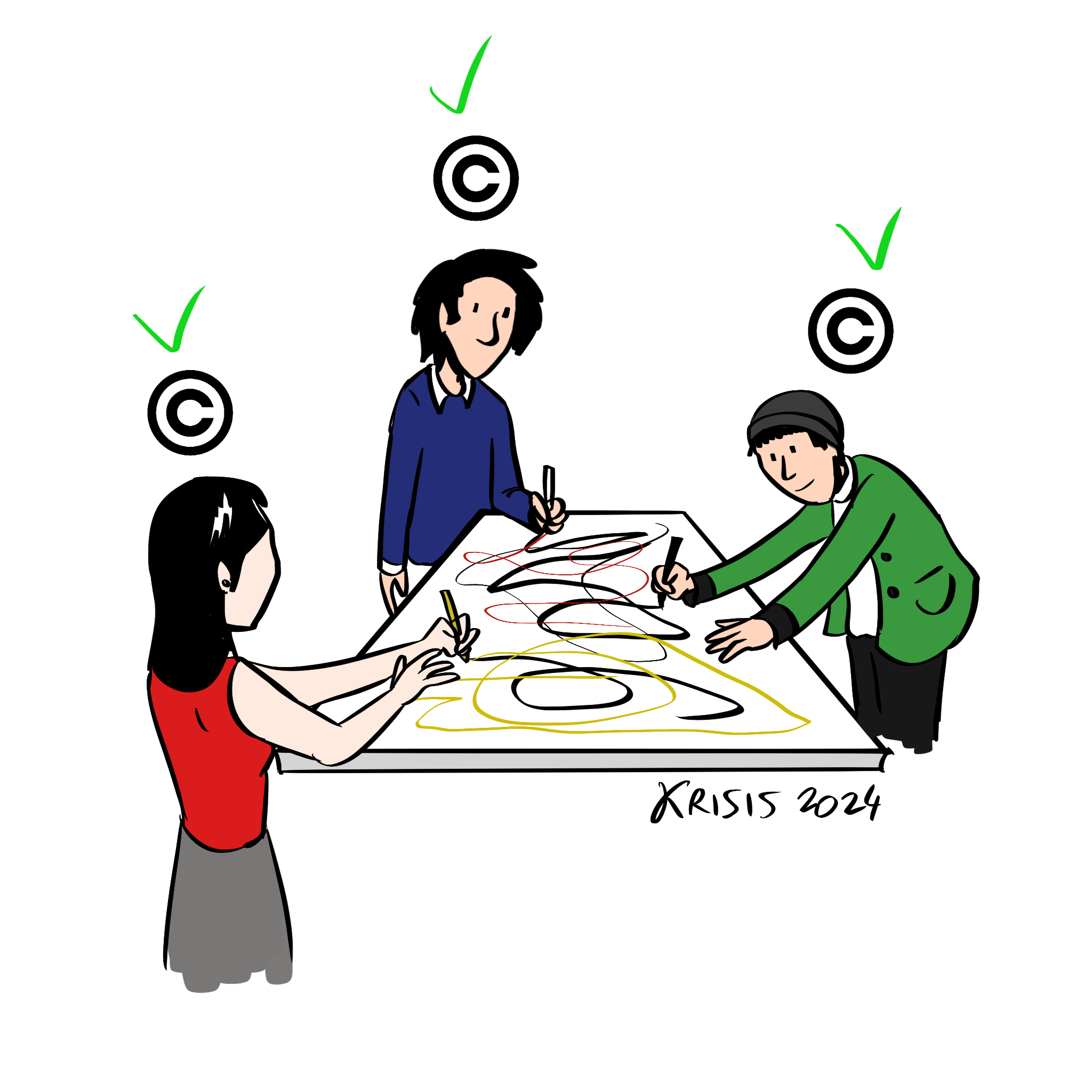

6.5.2 Multiple creators

Where two or more persons have contributed to the creation of one and the same work, they are entitled to joint copyright. This concerns a work that has been created by multiple creators whose contributions are inseparable. An example is a text that has been co-written by multiple persons. The creators obtain a single copyright on this, which is jointly granted to them. This means that the various co-authors must jointly decide on the exercise and management of the copyright. A licence or transfer of the right therefore requires the consent of each of them. However, in the event of infringement, each of the creators can independently enforce the right against third parties.

6.5.5 Transfer of rights

Copyright is transferred by succession. In addition, copyright is transferable. In the event of succession and transfer, the ownership position changes: the exclusive rights are transferred to another person. The creator thus loses control over the exploitation of the work. From that moment on, the exclusive authority to exploit the copyright rests with the person to whom the rights have been transferred.

However, the creator retains certain personal rights after transfer. This concerns the right to be named, the right to object to changes in the title or authorship, and the right to object to changes or infringement of the work. Due to the personal bond between the creator and the work, the idea is that these rights should always remain associated with the creator, even after the transfer of copyright. The creator can waive certain personal rights, such as the right to be named. Personal rights expire upon the death of the creator, unless the creator has appointed someone during his lifetime to exercise the personal rights until the copyright expires. Personal rights are regulated in article 25 Dutch Copyright Act.

Copyright can also be licensed to third parties. In the case of licensing, another person is given permission to exercise the copyright (for specific purposes), but ownership remains with the licensor. This can involve an exclusive license, with which the licensee obtains the sole right and the licensor may not grant competing powers to another person, or a non-exclusive license, with which the licensee only obtains a specific right of use and the licensor remains free to grant further licenses to another person.

It is important that transfer and licensing can concern all or part of the copyright. For example, copyright can only be transferred or licensed for specific purposes, user environments, distribution channels, branches or countries. This means that in practice the copyright can be split up and in this way can rest with multiple persons, each of whom manages a part of the copyright.

Copyright protects databases that meet the originality test (see Originality). For databases in which substantial investments have been made, there is a separate protection regime in the Database Act.↩︎